Happening Now

An Ideal State For Amtrak

September 11, 2019

Reauthorization Means It's Time To Wrestle With What 'Ideal' Means For A Publicly Funded Enterprise

by Jim Mathews / President & CEO

Skift is one of those new-breed online media companies, supplying news, research, analysis and marketing to the entire travel industry, everyone from air carriers to hotels and restaurants and everything in-between. Next week Amtrak CEO Richard Anderson is set to speak at Skift’s Global Forum speakers’ series in New York City, and over this past weekend Skift published a Q&A with Anderson which seems to be a preview of his talk.

The problem, as always, is framing. Skift started with the assumption that Amtrak has to make a profit like any other company. Skift's framing is incorrect, as I’ve written previously. Please go back and re-read what I said about the legal fiction that Amtrak must make a profit.

When you start with the narrative that Amtrak’s problem is that it’s forced to run long-distance trains at a loss instead of short-corridor trains in densely populated areas at an operating profit (a debatable idea), a lot of other assumptions come along for the ride and go completely uninterrogated.

Overall when I read the interview, I was reminded why I actually admire a lot of the tough calls Anderson is having to make at Amtrak. Focusing like a laser on safety, installing a safety-management system (SMS) culture and processes, forcing conversations among managers about efficiency…all of those are good things to do. And for the first time in a long time, Amtrak leaders are talking about truly growing service, adding to the offering and buying new equipment for the long-distance services and looking ahead to the future. Even if I disagree with the details, they need to be given credit for at least beginning to think about what it might take to make service better and more relevant to new riders.

But there’s a big, looming flaw: the notion that Amtrak’s routes need to be profitable to justify their existence.

I’m zeroed in on this part of the exchange between Skift and Anderson:

>>Skift: You make a lot of your revenue on short-haul trains on the East Coast. But you said the longer routes are more challenging. What’s their future?

Anderson: There will always be a place for the experiential long-haul train, because Congress has told us clearly that that’s an important part of our mission. What we do is follow the law at Amtrak. The laws are clear that the national network is an important offering.

Probably today, we operate 15 of them, including Empire Builder across the northern western half of the U.S., the Zephyr from Chicago to San Francisco, the Southwest Chief, and the Coast Starlight. In an ideal state, we probably would operate somewhere between five to 10 and instead focus our efforts and resources on short-haul intercity transportation, because that’s where the demand indicators are for Amtrak.<<

Well yes, if Amtrak were a true private corporation that’s exactly what you’d do. Which is why in the 1970s we almost had no long-distance service…because the “demand indicators” were suppressed by government subsidies of competing modes. The largely unsubsidized private railroads responded to those skewed demand indicators by dropping service.

But the people of the United States, acting through their elected representatives, decided there was more value to this kind of service than what was profitable to the railroads. So they created Amtrak, with the help of this Association. Amtrak exists precisely because there IS no ideal state. Amtrak exists, and collects public money, expressly to provide service to places that need it and where the private sector cannot profitably provide it…where the “demand indicators” aren’t enough to satisfy private shareholders.

Amtrak is one of the ways the U.S. government acts to support the common good, the “general welfare.” Every Amtrak long-distance route creates return on equity for the communities that have invested in it over the past few decades. And thanks to rigorous economic modeling this Association has developed over the past year, we have been able to quantify that return in a way that hasn’t been done previously.

The Empire Builder, for example, is worth $327 million every year to the economies of the states it serves, and by extension the entire U.S. economy. We pay roughly $57 million every year to run it. That’s a helluva bargain. For small communities along the route, it’s a lifeline. Just to take one instance, Cut Bank, Montana, and its roughly 3,000 citizens derive nearly $400,000 worth of economic benefit from the existence of the train.

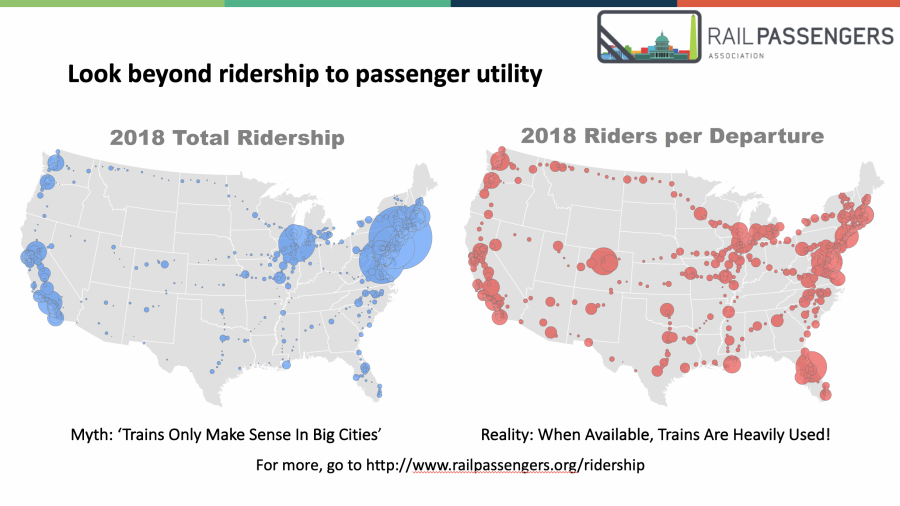

And the argument that only the Northeast Corridor is used enough to justify the investment falls away quickly when you look at it closely. Just consider the comparison between simply measuring the total ridership and looking at the number of riders per departure – i.e., if the train only runs three days a week, normalize the ridership figure to account for the four days that it doesn’t run. The slide below is one I use a lot to tell that story when I present to elected and appointed officials. The picture is indeed worth a thousand words, and shows clearly a National Network that is well-used and vital to communities across the country.

In the Skift interview, Anderson to his credit acknowledges and recognizes that the law supports a National Network, declaring that “we follow the law at Amtrak” and saying that “Congress has told us clearly that that’s an important part of our mission.” And that’s why it’s so important for all of us advocates to keep our eyes on the ball when Congress begins tackling the work of re-authorizing the next five-year surface transportation bill – the FAST Act.

Our coalition-building with Congress and key congressional leaders and staff has proven incredibly valuable on this score, especially in the past two years. Getting our language in to the appropriations measure preserving the Chief and the Network capped a lot of hard work. And today members of Congress have embraced our arguments about the economic benefits of passenger rail. That’s because we’ve been able to show convincing economic data around those arguments, not just philosophical platitudes.

We have good data on our side to illustrate the economic value of the Network, the return-on-equity which taxpaying communities all across the country are collecting each and every day because they get the service in which they have invested since 1971. This is the real “profit” of each route, being generated every day for communities around the U.S. from federal investment.

In an “ideal state,” BNSF, CSX, CN and the rest could earn a sufficient profit for their shareholders by ensuring that the elderly woman in Marks, Mississippi, the disabled vet in New Mexico or the isolated Native Americans in Montana all had safe, reliable service. But that “ideal state” doesn’t exist, and that’s why we have an Amtrak.

"Thank you to Jim Mathews and the Rail Passengers Association for presenting me with this prestigious award. I am always looking at ways to work with the railroads and rail advocates to improve the passenger experience."

Congressman Dan Lipinski (IL-3)

February 14, 2020, on receiving the Association's Golden Spike Award

Comments